Music of the 1970s:

A Record Store Education

Well, there is more than enough on

this site about my music so here is a

long and indulgent item about music in that decade that has made me happy or

has otherwise had some impact on me.

We live in an age when everyone is a

DJ and everyone carries their favourite music around in their phone. Nobody

wants to be told what is or was good or bad, so there is little point in

putting playlists together or telling anyone that they have poor taste.

Instead, I shall pick out a few items from my collection that have stories

attached to them. I hope it will make an entertaining read and if you encounter

even one record that you like; I will consider the exercise a success.

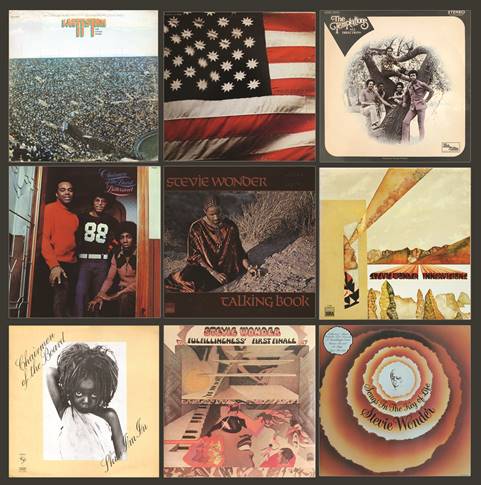

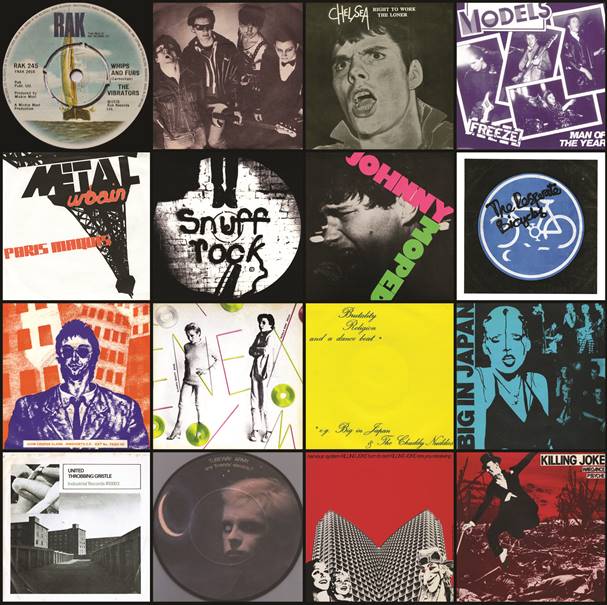

Top: Pop,

Prog, Krautrock and Rock 1970-1976-ish

Middle: Funk

and Reggae 1972-1976-ish

Bottom: Punk

and New Wave 1976-1980

As a child through the 1960s, music came with TV shows and on the few popular music radio shows that were around. My Dad played me Beethoven and Dvorak as did the BBC; my Mum often sang around the house; usually songs from film musicals, some probably pre-war. My elder (though not eldest) brother also became interested in classical music, though he preferred 'earlier' stuff; particularly JS Bach. My eldest brother was of the jazz generation; his youth misspent in smoky Soho clubs in the days before rock & roll came along and changed everything. None of this did me any harm, but as with all teenagers, I had to find my own thing.

My own thing turned out to be lots of things. I got really interested in 'current' music in 1972; listening fairly intently to the new 'Radio One' by day and Radio Luxemburg in the evening. Pretty-much all the content was based on the pop singles chart; there was, as I later discovered, a whole world of music going on in the UK, Europe and the US about which the 12 year old kid in Basingstoke was told nothing. Nevertheless, some representatives of this unknown world did sneak into the charts, particularly around 1972 when Hawkwind, Alice Cooper or Atomic Rooster could be heard amid the nauseous teen drivel of the Osmonds and David Cassidy. Artists known to the previous generation as crooners of sentimental love songs (Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, the Temptations) were now voicing their views about inequality, injustice and pollution. If these records appealed to me or provoked my curiosity, I had to actively search for further information from magazines and newspapers or by looking in record shops.

Before too long I was directed towards John Peel's radio shows which were on Radio One late at night. Here at last was the sound of that hidden, forbidden world or a substantial chunk of it at least. Peel seemed more concerned with getting an artist's music heard than he was with making them famous and getting them on Top of the Pops. Much of what he was playing on his shows in 1973 was folk music which I found dull and despite what he may have said in later life, he showed little interest in the soul music of the time or the funky jazz that was emerging. Two decades later, Peel said that when he had played a reggae record back in the day, he received lots of angry letters from his regular listeners. Thus it was to be a few years later, when punk arrived, that Peel was finally able to play anything he wanted, so whilst acknowledging the vital importance of Peel throughout my life, my love of reggae, jazz-rock and soul was acquired elsewhere.

Some of the celebrated artists of the early 70s had been championed by Peel, notably Bowie, Bolan, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Frank Zappa and Captain Beefheart, but they were now able to forge successful careers without his help. So what did I hear on his programmes in 1973 that changed my life? Progressive rock and krautrock were a complete revelation.

Progressive rock had yet to evolve into the stadium-filling monster that it became. Bands for the most part were poor and worked very hard and little of the music they produced sounded like it was intended to make them rich. It was art for art's sake; a noble sentiment and one that set them apart from Gary Glitter and their other pop contemporaries.

Gentle Giant had released Octopus in December 1972. It was their fourth album but the first I got to hear. The music was lively and unpredictable but it had a fascinating feel about it. Not every track was great but some really were. Stuart, my friend through Fairfields and Cranbourne, shared my interest in this music and we undertook the journey of musical discovery together; alternating between his handful of albums and mine as we did our homework. (Well, Stuart did his homework at least). Girlfriends didn't like any of it; not the grinding rock of Black Sabbath; not the melodic genius of Focus nor even the cataclysmic bombast of King Crimson. "I can't dance to that!" they would say. Stuart and I also liked music to which it was possible to dance but we found room in our lives for both whereas the girls generally speaking, could not. Krautrock was even further out on a limb and even less accessible to them. I bought quite a number of German albums after hearing them on Peel's programmes. Stu and I were never offered drugs and were smart enough to have declined them anyway although we both became cigarette smokers. The music was fascinating enough; it never occurred to us that we needed to be stoned to fully appreciate it and this might even have surprised the artists themselves.

Until the arrival of Subway Records (45A Winchester Street) in 1973 and Harlequin Records in the New Market Square in 1974, it was simply not possible (in Basingstoke or indeed anywhere in the UK) to buy the German records that Peel was playing. A previously unknown company named Virgin were very quick to establish a mail order service that advertised in the music weeklies and the very first of their eventual network of shops which was in London's Oxford Street. These were to remain the only sources of German records for a year or so until the rest of the country woke up. On at least two occasions we made trips to London on the train with just enough money to buy one record each. On our first visit to Virgin Records, we arrived at the Oxford Street address to find that it was a shoe shop. When we asked about the record shop that was supposed to be there, we were told that it might be those people upstairs. It indeed was. The shop was not spacious but crammed full of amazing music. It had wooden floorboards and the scent of patchouli filled the air. All the staff were hippies. Virgin did not limit their importation to German records; there were American and European sections and probably African and South American too if we'd had time to look. With our limited budget, it was probably best not to get too interested in anything but the records we'd come to look at.

Krautrock is often defined today by listing the more successful names that emerged from it but many of these now-household names (Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk) were then producing music which had no obvious connection to rock as such. Rock of the Kinks/Rolling Stones/Beatles strain was the basis of most of Germany's rock music of the late sixties but those that chose to defy the conventions unavoidably became associated with the German rock scene more generally; thus the arrhythmic experimentalists (Cluster, Popol Vuh, etc.) were perceived to be part of the same movement as the rock bands (Scorpions, Jane etc.)

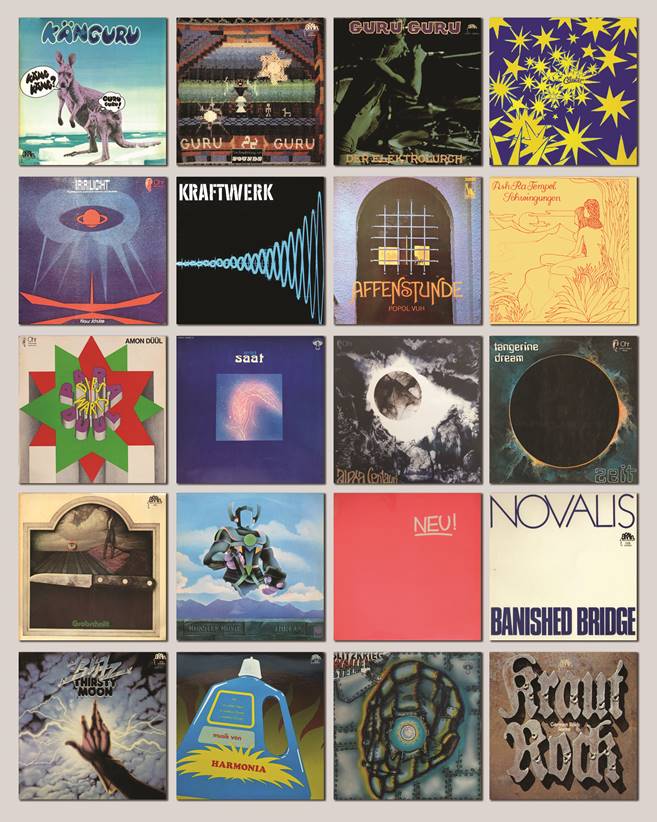

Below are twenty Krautrock albums that Stuart and I owned between us by the time we were sixteen. Most were acquired either from the original Virgin shop or from its mail order service.

Guru Guru were certainly among the first Krautrock 'bands' that Peel played. A quite extraordinary sound came out of my transistor radio; unmistakably rock music but where was the verse, chorus, verse, chorus structure we were used to? Although I was too young to figure it out at the time; Guru Guru took their lead from Jimi Hendrix but rather than simply copy his style or format, they created long, semi-improvised tracks that explored ideas within the rock & roll structures they'd grown up with. It was a moment that perhaps occurs in everyone's life; the moment when you said "that is the music I like".

'Kanguru' was released in December 1972 and was Guru Guru's third album. Peel had probably acquired his copy as a new release. Meanwhile, in Basingstoke my Mum was planning a visit to East London to visit my Grandmother and I somehow persuaded her that it would be a good idea to stop off at Oxford Street on the way. The Kanguru LP was a thing of beauty. Although the cover image was a bit quirky, the crisply laminated gatefold sleeve was so sharp and precise that even without the music, it presented itself as a masterpiece of cardboard engineering. The Brain label was an almost military green with black lettering. There were four tracks; each as spaced out and unpredictable as 'Baby Cake Walk' which Peel had played. The guitar was sometimes wild and sometimes played with great subtlety; the drums far more pronounced than in Hendrix's repertoire and percussive patterns sometimes took over and became the featured instrument; not unlike in Cream you might say; well, yes but no. Guru Guru, in that phase at least, owed more to rock 'n roll than the blues, even if Hendrix was their guiding spirit. The vocals (sometimes in German, sometimes in incomprehensible English) were often delivered in a voice like that of the Monty Python 'Gumby' character. Stuart bought their next album, an untitled fourth which was equally intriguing and absorbing.

In my childhood and youth, I committed quite a number of acts of utter stupidity; some grave, some not so. Lending records to complete or virtual strangers is something we should only ever do once but I was culpable of numerous further counts; the most painful of which concerns 'Kanguru'. Rather than receive it back, perhaps with a few bob for my trouble, I found it some weeks later in Bob Rivers' second-hand shop. The cover had been violently abused and coffee or tea had been spilled (or perhaps poured) on the record itself.

The heartbreak was not dissimilar to being 'chucked' by your girlfriend, just when you were getting along so well. Something approaching closure came a year or so later when the Brain record label reissued Kanguru and the 4th album together on a double called 'Der Elektrolurch'. Although the track order was changed for some reason or other, I was nevertheless able to get both albums in one at Harlequin and I, of course, still own it today but I never did run across the arsehole that did that to my record. A year or two ago I saw a copy of 'Kanguru' at a record fair. The dealer was asking £140 although that's not really the point.

Recommended? Yes, absolutely. I only acquired an original copy of Guru Guru's first album, 'UFO' at a car boot sale in Bramley in the nineties and neither Stuart nor I had been particularly keen on buying the second album 'Hinten' ('Behind') due to the slightly disturbing image of a man's hairy buttocks on the sleeve but the internet has made it easy to find Guru Guru's previous and subsequent work and it is perhaps inevitable that I should conclude that their third and fourth LPs (or the two together on 'Der Elektrolurch') were their finest hour.

Another early purchase was the LP Affenstunde ('Ape-hour') by Popol Vuh which was a name used by Florian Fricke who went on to make several albums before his death in 2001. This is notably different from his later albums in that it consists entirely of improvised synthesizer and percussion where his later stuff acquired an almost religious solemnity and was based around the piano or choral voices. Affenstunde was a rare disappointment frankly. A cynic might observe that it sounded like a couple of siblings who had been given a synthesizer and some bongos for Christmas and a disused church where they could make as much noise as they wanted. Their later LP Seligpreisung (1974) was far more satisfying if a little mournful in places.

The LPs Cluster 2 and 'Irrlicht' (the first solo album by Klaus Schulze) both arrived by mail order. The wait for their arrival was at times monumental but ultimately worthwhile. Cluster's second LP was described in a music paper of the day as 'coruscating electronics' and this term has never been improved upon. Largely improvised by a duo of lost musical souls; the music had no recognisable rhythm or beat but evolved organically like the sound of machines in a factory; responding to one another in a non-human way. On one of those occasions when the class is invited to bring in their favourite music, I played them a bit of Cluster. One of the other kids had brought in something by Wings and most of the others probably didn't yet own any records at all. What they would have made of the coruscating electronics is hard to imagine and my music teacher probably marked me down as a subversive or having come under the influence of some kind of satanic cult. (On another such occasion I took in Billy Preston's funky-as-fuck 'Outa Space' which one classmate described as 'repetitious'. Ah, those repetitive beats; who was going to put up with that?) Anyway, Cluster didn't have any beats at all, repetitive or otherwise.

Klaus Schulze was similarly devoid of groove but oddly mesmerising. He had, I later discovered, previously played in Tangerine Dream and Ash Ra Tempel but his first solo effort is a bruising trip down the galactic rapids with occasional moments of calm. And was that sampling? I'd always thought that it was a chamber orchestra that I could hear at the back of the mix doing a bit of Corelli or Handel.

Recommended? Cluster; yes but if you like that kind of thing you will already know them. Klaus Schulze? Yes, possibly, though he too requires the cooperation of the listener; his first albums, like those of Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk, were made before there was an audience to tell them what they wanted to hear, so they were aimlessly pursuing their own hazy objectives in defiance of what was expected of them as musicians and artists.

The Kraftwerk album is an exception to the coming through Virgin rule. Their first two LPs had been picked up by the go-ahead Vertigo label and re-packaged for a wider market, including the UK. The double LP was just called Kraftwerk and I bought mine in WH Smith.

John Peel had championed Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream before they became international artists even when the music they were making was nothing like the music for which they became famous. Apparently, Ralf Hutter, before his death in 2020, had dismissed the first three albums and declared that Autobahn (1974) was the first Kraftwerk release. As a kid who had saved up the £3 (most LPs were closer to £2) to buy these records or had travelled up to London to find them, I was kind of disappointed to learn that the artist would now wish to exclude them from his oeuvre and I think Peel might have felt the same. Nevertheless, I kind of get what he meant; the music on 'Kraftwerk' is simply unrecognisable to those that did not jump aboard until that synth-beat had redefined the artist, and the early stuff could be seen as their juvenilia or the workings-out in the margin, but to me, the experimental dabbling was a vital part of that Krautrock movement and I'd even go so far as to say that Autobahn marked a jumping-off point when interest outside Germany had led to a commercially-viable Krautrock.

The rhythm element brought these mad professors into a mainstream that was more easily accessible to the public ear and although I liked Autobahn and much of what Kraftwerk did subsequently, there was a feeling that the genie was out of the bottle. The fundamental difference between Autobahn and the previous work was down to computer-generated rhythms which had emerged with advances in technology that had not been available in the sixties. Moreover, drum machines came on the market and much of the stigma that might have been attached to working with a machine instead of a musician was moderated when some very credible artists (Sly Stone, Arthur Brown, Tony McPhee) took to using automated beats. True, a machine could not play with passion or feeling but maybe that's not always what the composer wants. The automated beat heralded a whole new thing which acquired a visual identity too. Kraftwerk evolved their trans-human image to complement the mechanised music. It was great and it was still Krautrock but seemed a very long way from that shoe shop in Oxford Street and that extraordinary flute music coming out of the radio (Peel had played 'Ruckzuck').

Recommended? No, not really. If you became a fan of Kraftwerk after Autobahn, you would find the first LPs disappointing. The music served a purpose in its day; it gave inquisitive schoolkids something to get excited about and provided a healthy alternative to the teenybopper nonsense we were fed. Some kids latched on to Slade or David Bowie, some to James Brown or Status Quo but some were bitten by the Krautrock bug; it appealed to a limited number of (mostly) young people in a specific place and time and it is impossible to recreate or reconstruct that context in order to help the listener appreciate the significance of any of these records.

Ash Ra Tempel was the project of a creative guitar-player and experimenter named Manuel Gottsching. My friend, Stuart actually owned at least two Ash Ra Tempel records though the stand-out was 'Schwingungen' ('Vibrations') which combined protracted quiet periods when nothing much happened with odd moments of bliss and full-on, drug-fuelled assaults on the listener. Recommended? Probably not; as with most of the vintage Krautrock LPs, its relevance has dissolved and listeners in today's crash, bang wallop 21st Century might be bored, confused or even mildly embarrassed by some of the content.

Amon Duul was a bunch or maybe a colony of hippies and 'Paradieswarts Duul', their third album, is entirely acoustic and meditative in nature but chaotically rhythmic like a spiritual Hawkwind with their electricity cut off. Recommended? Probably not but the basic Amon Duul split or redefined itself as a much rockier outfit named Amon Duul 2 and their albums were much more interesting. I had a copy of 'Yeti' (1970) though I always preferred the album that Stuart owned which was called 'Wolf City' (1972).

When Virgin Records first created its network of shops, Edinburgh was on the original list and while on a touring holiday with my Mum & Dad in Scotland, I persuaded them to let me go there and spend my holiday money on something frivolous and ephemeral and emerged with a copy of 'Saat' by Emtidi. Its selling point was its fabulous blue gatefold cover with mysterious and unearthly flowers but I had listened to some of it on some headphones in the shop and was not taking a punt (as I'd done with Affenstunde). The most striking thing about 'Walking in the Park' (the opening track) was the phased 12-string and the unmistakably not-German female vocal of Dolly Holmes; (the least likely name to grace the history of Krautrock). Dolly was apparently Canadian and 'Saat' was her second collaboration with German guitarist Maik Hirschweldt under the curious name of Emtidi. The record became a firm favourite and despite (or perhaps because of) its clever use of effects, was not one of the Krautrock records that caused adults to shrug their shoulders or shake their heads in despair. Decades later I got to buy a CD of Emtidi's first album which was lacking in ideas and would not have grabbed my attention the way that 'Saat' did. The difference was in the creativity of the record's engineer and producer who had evidently been hired to breathe some life into the act and make a silk purse from a sow's ear or whatever the expression is.

Recommended? Well, probably only the first side which features the epic 'Touch the Sun' which is wonderful hippy, trippy nonsense.

Tangerine Dream, just like Kraftwerk, were transformed in 1974, both artistically and commercially by new technologies and to a great extent, drew a line under their earlier albums. They had made four that had not been released in the UK before Richard Branson gave them a role in his emerging empire. As was also the case with Kraftwerk, the Tangs (as they became informally known) earned a global reputation for their creative use of technology and their later adherents will be surprised and disappointed at the primitive arrhythmic simplicity of the albums that got them noticed. The double album 'Zeit' (1972) was four sides of partly-improvised sound and arguably the first ambient record. It was undoubtedly the first rock record without any rhythm.

Grobschnitt was one of a number of German albums we owned between us that was every bit as 'rock' as it was 'kraut' so if your preference is for the former rather than the latter, I would recommend both Grobschnitt and the awkwardly-named Birth Control.

Can are one of Krautrock's best-known exponents. As their successful peers grew UK and US fan-bases, so did Can but they did not turn to computer rhythms in the way the others did. Indeed, why would you replace the brilliant Jaki Leibzeit with a machine? Technology did play a role in Can's evolution but it was Can's bass player, Holger Czukay that initiated the most significant change. His playing style had been a familiar characterstic of Can's earlier albums and gigs but he took to keyboards and became a pioneer of sampling.

I owned a copy of Can's 'Monster Movie' (their 1969 debut), some editions of which are now worth vast sums of money so I don't like to speculate too much about which edition it was or why I parted company with it. I also bought their 1973 album 'Future Days' when I heard Anne Nightingale play a track on Radio One. It was much more mellow than their previous excursions and would be my personal recommendation although devotees of the band would undoubtedly pick a different album.

In May 1973, Subway Records opened its doors. Stuart and I found it to be a place of enchantment and wonder. It was an independent record retailer run by two young men who were about a decade older than us. I soon got to know them and spent much of the Summer down in that magical cellar. Local muso Sugarman Sam called his 2016 album 'Record Store Education'. Mine was received at Subway. The shop stocked records of a specialist nature but catered for fans of soul, funky jazz, rock - heavy and progressive and later, reggae and Krautrock (largely at my suggestion). In this era, certain new releases kept the shop afloat; Tubular Bells and Dark Side of the Moon were often played on the stereo because casual browsers invariably asked what the record was and often bought it. Nevertheless, at thirteen, my new-found passion for music often resulted in skiving or bunking-off school to be where I was happiest. The shop went through some twists and turns and had gone by 1980 but in those seven or so years, Subway had been like an umbilical cord to the world of music; it was there that I had met Eddie and Phil with whom I started my first band (The Horizontal Bulgarians in 1978) and I still own some of the records I bought there but the knowledge it imparted to me has always been as valuable as that I received from my school.

Thus the arrival of Basingstoke's very own musical education centre coincided with the era in which Virgin was expanding its network of shops whilst now releasing records of its own. This was the time when those obscure German bands were coming to the surface; I could now buy records by Tangerine Dream and Can from a shop in my own town but as the years ticked by, Krautrock seemed to lose its sparkle and I had been introduced to whole ranges of new artists in genres that were not represented on the radio or TV.

When Subway had opened in 1973, its stock included a UK release of the first album by Neu! (The exclamation mark goes with the name). This was one of the Krautrock bands that Peel had played and the original German issue of 'Neu!' was one I'd had to forego for lack of financial resources but here it was with a different sleeve and I could listen to it on the headphones in the shop. The older guys didn't get it and although they were open to musical innovation and far from stuck in their generation, Krautrock didn't have the same effect as it did on me and Stu.

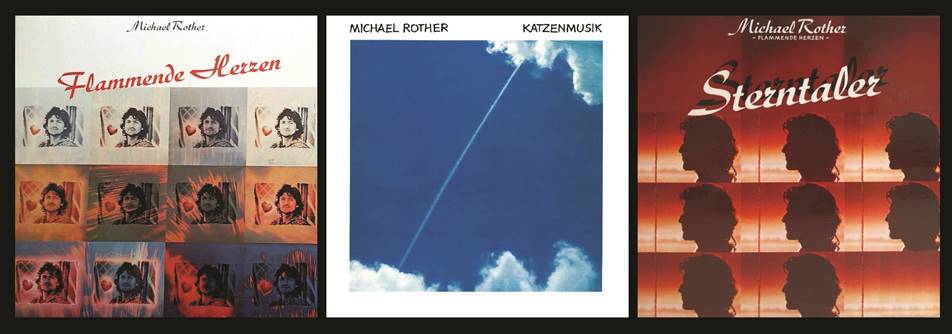

'Neu!' was different again to the Krautrock we'd already accumulated; it was mostly rhythmic but with a crazy drummer who was certainly not ready to be replaced by a machine. The music generated a kind of mood; often quite cold or distant and without any discernible pattern or structure. Stuart bought the second album; 'Neu! 2' for which, I later learned, there had been insufficient material. This had led to the decision by the Neu! duo and their producer, Conrad 'Conny' Plank, to fill a side of the record with speeded up or slowed down versions of tracks they had managed to finish. Their third album notwithstanding - 'Neu! 75' is regarded as a classic. The two members of this ultimately successful duo had both been working on other projects; drummer Klaus Dinger formed a new band called La Dusseldorf; guitarist Michael Rother worked with the Cluster duo under the name 'Harmonia' and went on to a fairly successful career as a maverick solo artist.

Would I recommend Neu! to newcomers (or neucomers)? Well, again, if you have the least interest in Krautrock, you will already know about Neu! I suspect though that the trippy repetition in their introverted instrumental sketches would be greeted in the same way by the Foo Fighters generation as it was by those who grew up with the Beatles and Stones. The track 'Isi' from 'Neu! 75' quite often crops up on 6Music and is certainly among their more mellow and accessible work. I have the first five of Michael Rother's solo albums; the sleeves of which tell the tale of a lost and anonymous hippy character who was groomed (in the nicest possible way) for a career as a smart and marketable composer. Although Rother's work probably drops just outside the Krautrock border, I heartily recommend 'Flammende Herzen' (1977), 'Sterntaler' (1978) and 'Katzenmusik' (1979).

When Subway brought in a batch of German imports, probably in the latter part of 1973, I made a few more Krautrock purchases; notably by the jazzy rock outfit, Embryo (which I wasn't very keen on and re-sold) and the first LP by Novalis - 'Banished Bridge' (1973) which was symphonic rock in the Pink Floyd vein. Although neither this album nor any of their subsequent offered the challenge provided by either Pink Floyd or any of Novalis' German contemporaries, I've kept Banished Bridge in the impeccable white gatefold sleeve it was given and I added their second eponymous LP to my collection on a visit to Berlin in 1976, about which I shall now tell you.

My Brother was on a University link course, studying German in Berlin. When school finished (for good) in 1976, it was proposed that I should jet over to keep him company for a couple of weeks. As it turned out, he shared a flat with a young lady and I was a bit of a gooseberry but it was an interesting and eye-opening trip and one that could not have been justified without the purchase of three records at least.

My prime directive was to find a copy of Emtidi's 'Saat' which I had carelessly swapped in a schoolboy-like deal with Stuart. That particular search proved fruitless even after going to look for the offices of the Pilz label which had either moved or been wound-up. I went into quite a few record shops but my three purchases were all made at a huge book and record retailer called Bote & Boch. As well as the second Novalis LP, I bought a 1976 album called 'Blitz' by Thirsty Moon and the now-legendary 'Musik von Harmonia'.

Despite being released two years earlier, my copy of Harmonia's album was (and is) an original green Brain edition. It was first reissued in 1977 on the new orange version of the label and and has been rereleased many times since. This was Michael Rother's collaboration with the Cluster duo of Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius. One of they new-fangled drum machines was involved in the recordings which put them on an equal footing with Kraftwerk and Tangerine Dream in terms of technological advance but Harmonia's budget was considerably smaller and they evidently preferred to disguise the automaton's raw default sound and work around its rhythm rather than to it.

The 'Blitzkrieg' album by Wallenstein was the item I got for 'Saat' in the exchange with my friend. This act of folly led to nearly two decades of hopeless searching that finally ended in a record shop in Noho (the less interesting north side of Oxford Street) in 1995. It was surprisingly affordable and filled a monstrous hole in my life. I learned much later that I'd got the 1981 reissue but it had served its purpose and by then and had been cordially re-accommodated in my record collection irrespective of the authenticity of its issue and it is, in any case, indistinguishable from the 1972 edition save for a minor detail that only the most fastidious of anoraks would have noticed.

Wallenstein's album is excellent though and I'm delighted to have it still. It is on the same label as 'Saat' but is decidedly rock in essence although the mostly-instrumental tracks are played in a kind of jazz format where different players take extended lead breaks and improvised solos. Sometimes the band plays at break-neck speed and reaches the kind of paroxysm that one might expect from a live album. Great stuff!

The last of my selection of records to do your homework by (that isn't the title but could have been) is a 1974 Brain Records compilation that Stuart bought (I think) in Harlequin. 'Kraut Rock; German Rock Scene' was a triple album featuring no fewer than eighteen artists, many of whom I have mentioned above. This was quite a revealing snapshot of the two previous years and highlighted Brain's broad musical scope; the music we now call Krautrock was presented alongside the music we used to call rock. This triple LP is totally and thoroughly recommended.

There were a few other records or bands I could talk about but these are the German records that mark my Krautrock voyage of discovery. Though I'd never call myself an expert or authority on the matter, I am nonetheless an aficionado and something of a purist. My Krautrock consists of the two phases I have tried to identify; the pre-73 experimental phase and the post-73 export drive. The latter, in my humble opinion, shed its roots and became part of an international mainstream which was, itself to be overhauled with the arrival of punk in 1977.

Krautrock is widely used as a generic compartment that includes avant-garde or experimental artists from anywhere and across half a Century. Personally however, I feel a bit nauseous when an ensemble formed in Basingstoke in 2000 and whatever declares itself to be 'a Krautrock band'. I wonder though whether there might be Krautrock tribute bands out there; recreating those coruscating electronics with authentic malfunctioning low-budget equipment; emptying theatres and sending audiences away in their droves, just as their heroes had done.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you've got this far and you are still conscious, you might have the impression that Krautrock was the only stuff I listened to in my youth; not so. Here are some of the more easily-sought records of the early 70s; ten American albums, twelve from the UK plus a bunch more European favourites.

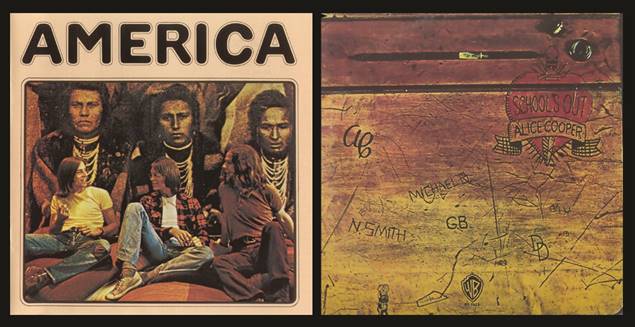

'A Horse with no Name' is remembered across the generations though it has often been the subject of jokes or criticism. As a schoolkid I had taken to listening to Radio Luxemburg and this moody, plodding single by America seemed to stand out from everything else. In fact the radio station declared it their Christmas No. 1 in 1971 despite the fact that it was being outsold by Benny Hill's 'Ernie'. They clearly believed that it merited the place because it was a better record and I totally agreed (and still do). I requested it as my Christmas present (with something I could play it on) and drove my parents insane with this lethal combination of machine and disc. (They might have been grateful that I hadn't requested 'Ernie'.)

America's eponymous debut LP soon followed and it absorbed me in the same way as people were absorbed by Simon & Garfunkel or Leonard Cohen. The lilting harmonies with which the band were identified, were certainly present on the album but not laid on with a trowel as they were on later releases and the songs, though relatively simple, conveyed a range of moods. As time went on, I became a bit more discriminating about the individual tracks; eventually selecting 'Riverside', Here', 'Rainy Day', 'Never Found the Time', and 'Clarice' for the i-pod.

Not long after, another Warner Brothers artist burst onto the pop scene and maintained rock music's presence in a world dominated by sentimentality, teenybopper slush and bogus rock 'n roll revivalism. Alice Cooper was the slightly unnerving name (at the time) of a band/individual with a kind of Hammer Horror stage show. 'School's Out' was certainly not his/their first single or album but both launched the Alice Cooper brand in the UK.

It may seem an odd comparison but another figure that was coming to our attention at that time was David Bowie. The latter was, of course, to build a huge fan base, initially in the UK through the depth and bredth of his talent and imagination while Cooper's impact was immediate and always going to be hard to follow up. The 'School's Out' single and album addressed us directly; Cooper sang like he was one of us; hated school; couldn't wait to get away. The LP however, whilst continuing the school rebel theme, also betrays a nostalgia for the time you said goodbye to those old friends and there are some quite touching moments among the guitar-driven furore. There is more light & shade than I've noticed in previous or subsequent Alice Cooper albums. The cover was designed like a school desk with names scratched into it, with an opening lid that revealed the record. The Discogs notes about School's Out tell us:

"The vinyl record inside was wrapped in a pair of panties (not included in the European versions), though this was later discontinued as the paper panties were found to be flammable." Yep, no knickers with my copy but it's stil Alice Cooper's outstanding contribution to my life.

As for Bowie; yes, all of us liked him but some were more inclined to form a kind of cult around him which wasn't for us Krautrockers. Indeed, though I had my own heroes (mostly musicians and footballers) my admiration never grew to adoration or veneration or any other kind of ation.

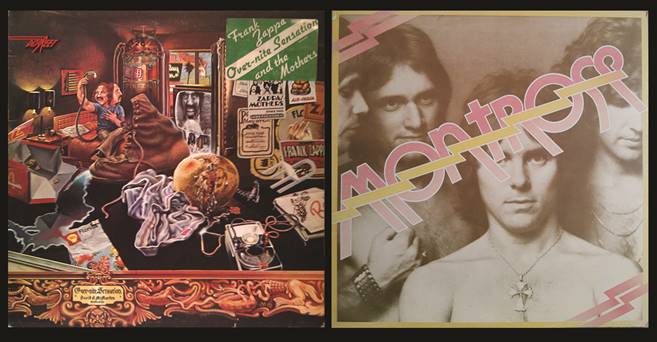

My introduction to Frank Zappa came in 1971 when a family friend played me 'Hot Rats' which was probably a bit overwhelming at that age but when 'Over-nite Sensation' happened along, young hetero males took to its unapologetic sexism even if the music would have been just as good without it. The nagging, meandering guitar solo in 'Montana' was always the album's highlight.

This seems like a good juncture to talk about 'blokeyism'. In the 70s, issues around homosexuality and gender were never discussed by kids to whom they had no relevance. Such talk caused uneasiness and often provoked revulsion; real or synthetic. There were certainly gay lads in our midst but they would often be teased merely on suspicion based on their mannerisms or speech. The attitudes that prevailed among the straight majority were probably those of our teachers as well. It was largely down to Bowie that these attitudes began to shift. His sexual ambiguity was a stark contrast to the likes of Frank Zappa who celebrated maleness through their words and music. The history of popular music to that point was dominated by men; Sinatra, Elvis, Beatles, Stones, James Brown, Led Zeppelin, Slade; the unwritten rule was that blokes made music and the girls bought it and danced to it. Bowie himself was a perfect example but he nevertheless pioneered the present day normality in which 70s music is perceived as having been produced in a tunnel of ignorance.

There were female artists throughout that time of course, but they were often thought of as female equivalents of their male contemporaries; Joan Baez was, by default an unwitting, unwilling Jane to Dylan's Tarzan; few women expressed themselves sexually in the way that Jagger or Lennon did (at least until Janis Joplin, Tina Turner and Millie Jackson emerged) and pop music generally was accepted as being a blokey industry in which women were occasional contributors. 'Normal' was four schoolmates getting together to play the kind of music they'd been listening to and their prime directive was to impress and win the hearts of the girls. It was a formula that worked well for a pop industry that looked at girls as consumers. Talented young girls could be successful but either as singers in otherwise-male bands or as interpreters of songs written and chosen for them by men. For whatever reason, girls and women were not associated with the landmark rock albums and few of their gender took the artistic risks of Pink Floyd or Soft Machine or added their angry voices to those of Stevie Wonder or Marvin Gaye. The experimental work of Daphne Oram and her colleagues at the BBC was largely behind the scenes and until more recently unrecognised though nonetheless an exception to the rule of the male-dominated sphere of music-making. Progressive music and heavy rock epitomised male prominence as well as any genre; these were favoured far more by the non-dancing geezers than by the singles-buying girls.

While I have no intention of mitigating or apologising on anyone's behalf, it is a bit unfair to point fingers at well-meaning musicians who were simply doing and writing what they understood to be acceptable. Even in the right-thinking 21st Century, it is perfectly acceptable to form a group with other hetero males and sing to impress the girls even if this is no longer the unique formula that it once was. The blokes that bought the blokey music did not buy it to reinforce their prejudices; we made and bought music that we loved and there is no right or wrong reason for that.

The eponymous Montrose album (1973, posted above) was something of a landmark and one of a few albums that paved the way to stadium rock and is seldom overlooked in retrospective charts of important rock records. Surprisingly, none of Montrose's subsequent releases got anywhere near recreating the power generated on the first. It seems like a case of guitarist Ronnie Montrose having his entire life to come up with ten fabulous riffs and six months to come up with ten more. It is the grating chainsaw guitar that burrows into your head and the drums (given the same vastness as those of John Bonham on Led Zeppelin's records) that announce the arrival of stadium rock. The singer on 'Montrose' is Sammy Hagar who went on to front his own stadium-filling band.

'Montrose' is 'compulsory' rather than 'recommended'.

These are two records I played a lot as a lad that both feature guitarist Dick Wagner. Peel had played the opening track 'Sinner' which grabbed the attention but I had to order a copy of 'Ursa Major' as a US import. It was (and is) an interesting LP; effectively Wagner's solo album with notable contributions from his drummer, Greg Arama.

Lou Reed's career went through a number of phases. In the 70s he was promoted as a major star and found himself playing stadia and huge venues. This is a period in his life and career that fans of the Velvet Underground might prefer to disregard but the live album, 'Rock 'n Roll Animal' (1974) was a firm favourite at Razzle Villas. Reed's transition to stadium-filler required making him bigger and louder so the band that formed around him did not share his art school background. Perhaps Reed purists disliked the idea that the Velvet Underground's rebel New York street poet had formed an alliance with musicians of a different tradition, but this was no sell-out; the band were top players and the music was great.

'Rock 'n Roll Animal' provides one of those wonderful rock moments that I will now ruin for you: Lou's twin guitarists, Dick Wagner and Steve Hunter launch into a kind of instrumental duet; pretty and delicate like two butterflies skirmishing in a woody clearing and on they go for a full three minutes before the music, almost imperceptibly becomes the riff to Sweet Jane. Then you hear the audience burst into life and you are virtually there as Reed takes the stage. Try it.

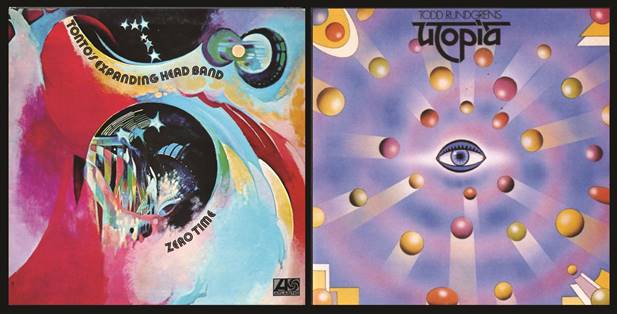

Here are two American albums that put synthesizers at the forefront but in entirely different ways. Tonto's Expanding Head Band was two advanced dial-fiddlers named Margouleff and Cecil. Their 1971 'Zero Time' album was made entirely with electronic machines, perhaps like some of their contemporaries in Germany and Europe but their product was a revelation to some ears with its carefully constructed collages of unearthly sounds and even a ghostly computer-generated voice. The pair went on to programme synths for Stevie Wonder in 1972 and 1973 and recorded another Tonto album in 1974 which was inevitably not as good.

Todd Rundgren's career has been immense and there is little I can tell you that you don't already know but you can imagine that once discovered, this multi-talented multi-instrumentalist and producer was a ready-made hero. Utopia was a band that Rundgren put together after making at least four solo albums. The second side of Utopia's 1974 debut was a thirty minute quilt of tunes, themes and songs which ends with a grandiose finale made up of the themes that had occurred in the previous half-hour; brilliantly edited together by an evident genius.

The final two of my ten US albums of the early 70s both came out in 1976 (the year I left school) and they reflect, better than I had expected, just how tame rock music had become by then. I've always liked both these records but seen in retrospect, they lack the punch and excitement of my previous choices. This corresponds with the stale period in the middle of the decade to which punk was to be the antidote. JJ Cale's music epitomised the term 'laid back' and was country rock that had by that time acquired a funky element. Hejira was Joni Mitchell's umpteenth album and she was now the mature, established Canadian songwriter with a backing band of experienced musicians. Both fine records, no question but there had to be something new on the horizon...

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Before considering what exactly was coming over the horizon, here is the same account of 1971 to 1976 but told through twelve UK records. Choosing favourites from each side of the pond was fairly easy and it becomes clear that the US/UK market share was about even in that period.

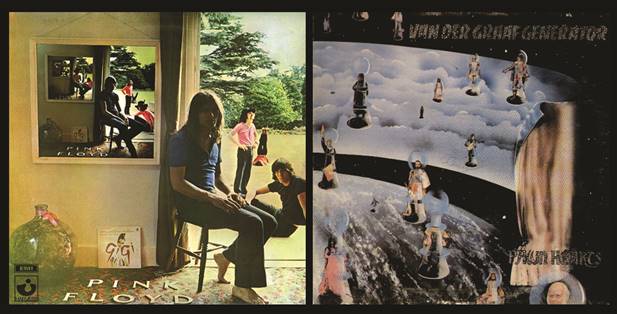

Pink Floyd's 'Ummagumma' was released in 1969 but Stu got a copy when Peel played Astronomy Domini on his show probably in '72 or '73 but certainly before 'Dark Side' came out. This and the Meddle album remained in favour throughout our school years. 'Dark Side'? We liked it well enough but it is one of those albums that I have heard too many times. Van Der Graaf Generator's Pawn Hearts LP (1971) was also acquired a while after its release, quite possibly from Ned Scrumpo's Emporium (run by the previously-mentioned RF Rivers). The VDGG soup was one into which I occasionally dipped. I came to regard Peter Hammill as a would-be Bowie; clever and imaginative but his material was too dark to have made him a chart-topper and he didn't reinvent himself with new haircuts or teeth (or if he did, it escaped the notice of most of us).

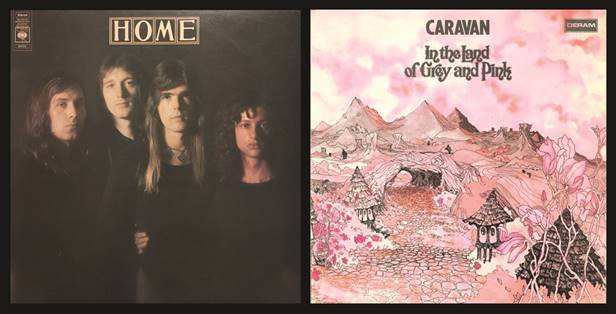

Home was the first band I got to see live (although strictly speaking, the second as they were supported by a band called Snow Leopard). This was March 30th 1973; about two months before Subway Records opened and I believe their eponymous second album was my first Subway purchase. The opening track 'Dreamer' had also been their opener at Basingstoke Technical College ('the Tech' as it was known). The rest of the LP was less spectacular but can make a pleasant listen. When Home broke up after their third album, Cliff Williams became the bass player for AC/DC and guitarist Laurie Wisefield joined Wishbone Ash.

'In the Land of Grey and Pink' was another LP that Stuart acquired either second-hand or as a second edition. It was quintessentially English music that nevertheless supplemented our Krautrock homework soundtrack. The second side is a single track broken into songs and instrumental passages that featured a distorted keyboard flowing through them. After a few listens you could find yourself whistling the complex breaks and solos right through the twenty-two minute duration of Caravan's 'Nine Feet Underground'.

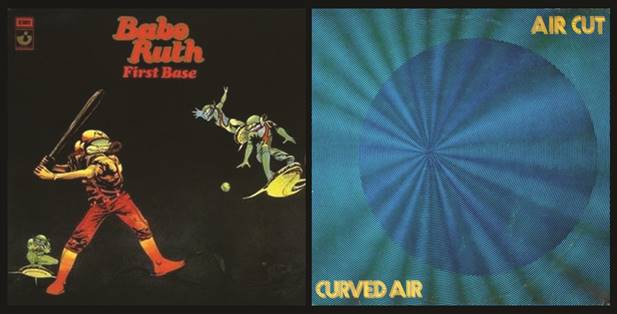

Babe Ruth and Curved Air were two favourite bands of my teens. They both serve as examples of blokey 70s rock with female vocals. Babe Ruth's debut, 'First Base' featured six tracks spread over two sides, each of them with some merit. Their rendering of Jesse Winchester's 'Black Dog' ends with an intense guitar/vocal duel/duet that prompted one young lady friend to say "it makes me want to smile and cry at the same time". Apparently Babe Ruth's interpretation of Morricone's 'For a Few Dollars More' has frequently been sampled (although never by me) and the track 'Joker' shows the band at its most raw and raunchy although my favourite was always their semi-improvised instrumental reinterpretation of Frank Zappa's 'King Kong'. Further albums were OK too though First Base had set the bar very high. Singer Janita Haan was a blend of Cleo Laine and Janis Joplin. I was to meet her and bass player Dave Hewitt when they appeared as Jenny Haan's Lion at the Tech in 1978 but the band never released anything and they dropped off the radar.

Curved Air are still performing and recording fifty years + after their first incarnation in 1970. All their early albums are interesting although their line-up changed constantly. Only singer Sonja Kristina has remained throughout. Most devotees would cite 'Air Cut' (1973) as a favourite; it brings together Kirby's venomous guitar and Eddie Jobson's lyrical piano, particularly in 'Metamorphosis'. Previous albums had largely relied on the unique violin pyrotechnics of Darryl Way. Curved Air proved that progressive rock did not have to be entirely blokey and they had kindred spirits in the symphonic rock band Renaissance, but female vocalists were more often found in hard rock bands such as Stone the Crows and Vinegar Joe or folk ensembles such as Fairport Convention and Steeleye Span. The best-known female singers of the mid-70s emerged with or from pop groups (ABBA being the most obvious) until Kate Bush, Chrissie Hynde, Siouxie Sue, Poly Styrene, Debbie Harry and Tina Turner opened the door to a less blokey future.

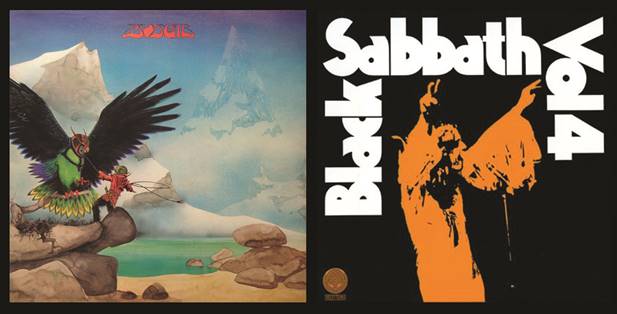

Meanwhile, back in the blokey years of the early 70s, guitars were getting louder and a full-on sustained electric sound became default for rock bands across Europe and the US. If Black Sabbath didn't trigger this trend, they certainly exploited it as well as anyone. Vol 4 was my introduction, not just to Black Sabbath but to that overloaded buzz-saw guitar sound. As a listener to Radio Luxemburg at the time, such music rarely came my way but 'Tomorrow's Dream' had been issued as a single and a Luxy DJ played it on a show quite early one evening and it stood out from everything like a big standy-out thing. I bought my Vol 4 in Gifford's shortly before the record department was closed down. Previous and future Black Sabbath records were investigated and purchased. I would not venture to nominate the band's best album but Volume Four is a stonker.

We also got records by Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple but to all the heavy rock bands I would apply the same rule of thumb as that for everything else; any artist that recorded throughout the seventies had made their best albums by 1974.

Budgie's unique sound was mostly due to Burke-Shelley's high-pitched vocals as much as Tony Bourge's grinding guitar although they were in some sense typical of British rock bands of the first half of the decade; touring and recording constantly and jumping at the opportunity to appear on the Old Grey Whistle Test which is where Budgie came to our attention. The OGWT was often a disappointment to those of us who were getting into this Krautrock stuff that Peel was playing. Bob Harris always had more conservative taste than Peel and many of the artists that featured on the OGWT were dull and these were often American West-Coast acts that we found uninteresting. However, not to throw baby out with bath-water; it definitely had its moments.

Discovering rock music was largely a shared experience for my school friend, Stuart and me. For a start it doubled the number of records that we could listen to even if we didn't automatically like each other's choices. Sometimes we might have disliked our own choices but finding what you like inevitably involves discovering what you don't like. Both of us loved these two albums: Arthur Brown's Kingdom Come came to us via John Peel while the first album by Camel was a popular choice on the in-store hi-fi at Subway.

Kingdom Come's 'Journey' (1973) was clearly the work of an inspired eccentric. We already knew Arthur Brown's 'Fire' hit from a few years before (it was often played as an oldie on pop radio) but Peel was a firm advocate of the Kingdom Come project. 'Journey' was the band's third album but it introduced us to the drum machine; inviting us to accept it or reject it. The politics of replacing a drummer with a machine were not immediately apparent to school kids; to us it just sounded different to everything else and besides, the drums were only part of the construction of the music; it was the vocals and guitar that sold it to us and for which it will ultimately be recommended. Use of technology in popular music was becoming part of the new normal and we embraced it but only in the certain knowledge that drummers would continue to exist and thrive in parenthesis with the machines rather than recede to becoming ancient craftsmen like glass-blowers or thatchers.

Meanwhile, the newly-formed Camel was the least likely band to turn to technology for its rhythm section although their identifying feature was the interplay between the guitar and organ. Indeed the vocals on 'Camel' (1973) are never forceful and sometimes even seemed to be there to provide an alternative to the intricate instrumental work for which they were later celebrated. It rocks too in places but its changes in tempo and mood are conducted by a band that sounded as though it had been together far longer than it had.

Camel were one of a number of bands we saw at the Tech but their story has a certain historical significance, not least to two rock-hungry teenagers in Basingstoke. With the splendid debut nestling comfortably in the record rack, Stuart grabbed the second album, 'Mirage' upon its release and we became enthused by the prospect of seeing this band at our local Tech College.

Stuart took along the insert from Mirage. At previous gigs we had sought permission to go backstage and meet the bands and the privilege on this occasion was granted but suspended pending some politics or technical issues. This was either on the 2nd or 5th April, 1974. Camel websites are uncertain about the date and I haven't found an advert in the Gazette to confirm it but I was there and vividly recall the Tech auditorium packed (as it sometimes was) but with angry people - mostly blokes of course, who had been told, by some brave soul, that Camel would not be performing. "We want Camel" they chanted. It wasn't really a frightening or threatening scenario even for two 14-year olds, but we sensed the anger and probably, in a less vociferous way, shared it. Our ardour was possibly tempered by the fact that we had seen various members pass us in the corridor on the way to the bathroom and that some kind person in the Students' Union had taken Stu's Mirage insert into the holy changing chamber and got it signed by all four original members. The audience was told that there was a technical hitch with their mixer which an older punter at the gig had described as "nonsense"; he knew for sure that his mate in the local band 'Orgasm' would gladly have supplied his mixer at the drop of a hat. The disappointed audience claimed back its entry fee as it mumbled about financial or contractual issues being a more likely explanation for the band's non-appearance. I don't know if Stu kept his trophy; I like to think so and I like to conjure the scenario on the other side of the changing room door; Camel might not have been in the right frame of mind to be signing autographs for fans but they nevertheless obliged and bless 'em for that.

As a post script to the Camel mini-saga; friend, musician and all-round-egg Marcus Nason announced in September 2018 that he had two tickets for a performance by Camel at the Albert Hall but was unable to attend. Ann & I duly bit his hand off and although only guitarist Andy Latimer remained from the 1974 line-up, it was a great night and a performance I'd awaited some forty-four years.

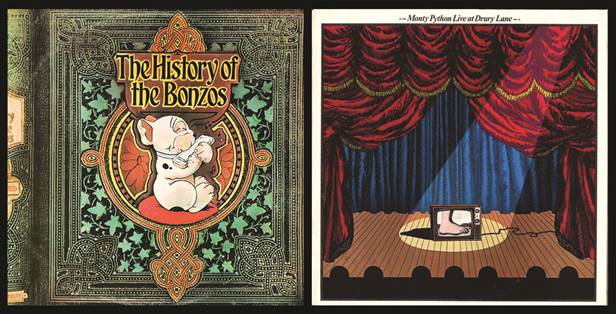

Humour has always been important in my life as I'm sure it is in yours. While TV offered us Morecambe & Wise and some pretty-awful sit-coms, younger progressives like us looked to the Goodies and Monty Python for our laughs. Sometimes this comedy transferred comfortably to records from which sprang ridiculous catch-phrases that we might use randomly in irrelevant circumstances. Monty Python's Live at Drury Lane LP (1974) is packed with such catch-phrases and dialogue that seemed even funnier when you knew that other kids were digesting it with equal fervour. Yes, bits of it make uncomfortable listening today but Python did not exploit racism or homophobic prejudice in the way that mainstream comedy was doing; if anything, it was the ill-educated or the over-educated racists and homophobes that were being lampooned. Python's strength was its 'outside the box' thinking and often surreal ideas.

"Is this the right room for an argument?"

"I've told you once!"

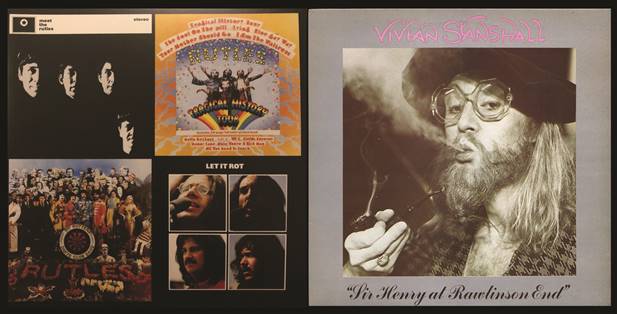

The Bonzos were best known for their novelty hit, 'I'm the Urban Spaceman' in 1968 but their various albums had escaped my notice until around 1976 when my eldest brother unexpectedly came home with a copy of 'the History of the Bonzos' (1974). Their history, as I perceived it, was of a kind of Lennon/McCartney of comedy songwriters named Neil Innes and Viv Stanshall. With the greatest respect to the other illustrious members, it was Innes & Stanshall who hatched their best ideas. Viv Stanshall portrayed himself as an English eccentric with a voice that invoked the Boer War or the Raj, although, as with Python, the figure he portrayed was an anachronism and not the least bit heroic. Stanshall's musical preference was New Orleans jazz which served quite a chunk of the Bonzos' recorded output whereas Neil Innes was far more 'with it' and in touch with the music of the day; at times parodying Pink Floyd or other psychedelia. Indeed, when the Bonzos split in 1970, Innes enjoyed a modestly successful solo career punctuated by his involvement with Eric Idle and Monty Python and the subsequent Rutles project for which he wrote a brilliant set of Beatles parodies. Ann and I got to meet Neil Innes when he performed to a tiny audience at Fairfields Arts Centre, and again nearly two decades later when he performed in Godalming with the erstwhile Rutles in May 2018. He died in December of the following year aged 75. Stanshall had died in 1995.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Before we leave the rock arena, here are some other European selections that played a part in my record store education. At around the same time as the German bands began making their mark internationally, new names sprung up from other European sources. We were naturally receptive to them. The French bands that spring to mind are Gong, Ange, Magma and Catharsis. The former became very popular with hippy revivalists (60s hippies were seriously unfashionable by 1973) while Ange's UK tour included a date at Basingstoke Tech (I missed that one) but French rock did not have the impact of other European exports; Italian, Dutch and Scandinavian bands figured more prominently.

First out of the blocks were Premiata Forneria Marconi who, not surprisingly, were billed as P.F.M. Their discography can be quite confusing as much of the material presented to the UK had already been recorded and released with Italian lyrics. The band signed to the Manticore label which had been set up by Emerson, Lake & Palmer (erm, ELP) and English lyrics were written (for all, most or some of the songs) by Pete Sinfield who had been one of the writers for King Crimson and was to record his own Manticore album, 'Still' with assistance from Greg Lake. There was considerable excitement at school about the release of PFM's single, 'Celebration' but I think this was generated largely by the music press that other kids had been reading. I honestly don't remember if Peel featured it but he always disliked ELP so was less likely to have supported PFM.

The much-anticipated single was excellent; full-on cantering prog with the flavour of a country dance. It has a little breakdown in the middle with a poetic reflection and some flute and puppet-show piano before building back to its roistering chorus. Celebration remains a joy although the 'Photos of Ghosts' LP was not as immediate. However, the follow-up, 'The World Became the World' is packed with haunting themes and phenomenal solos. The title track includes a passage that suddenly goes from being very quiet to extremely loud (radio station sound engineers have been struggling to deal with it for nearly fifty years). A live album followed (released in the UK under the title 'Cook') which demonstrated that these extraordinary musicians could reproduce this complex and subtle music on stage.

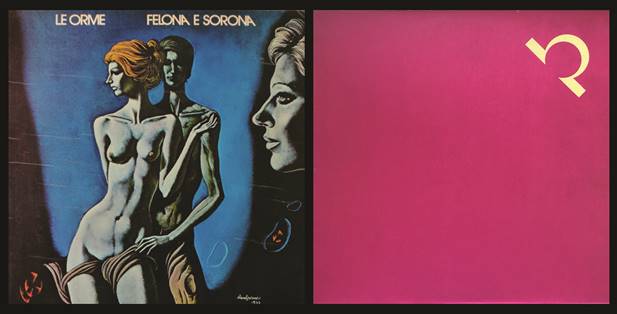

Hot on the heels of PFM came Le Orme. They too had a history of releases in Italy but their sci-fi-themed concept album 'Felona e Sorona' was re-recorded (with English lyrics by Peter Hammill no less) and issued by Charisma in 1973. This is generally considered their best album even by those that know Le Orme's catalogue and is certainly the only album known to UK prog fans. Its outstanding qualities are the intriguing lyrics delivered in a chorister-like voice and the creative use of keyboards but I wonder whether some guitar work might have given it more texture.

Omega, as I understand, are Hungary's gift to the world of rock. The apparently-untitled album with the stark red gatefold and the symbol in the corner, first leapt to my attention when it was filed or mis-filed among the Krautrock. Apparently it was their eighth LP and it has been reissued many times but with notable variations in the shade of red. The copy I first saw had a ferocious pillar-box hue and was quite probably the first record cover I ever saw with no image, words or text on the front cover (the Beatles' White Album had passed me by and does, technically speaking, have words on it and despite Stuart owning a copy of Led Zeppelin's so-called 'Four Symbols' LP; we in our blissful ignorance, knew it as Led Zep 4, and that certainly has an image on it anyway).

The Greek band Aphrodite's Child came via a single titled 'Break' and a track called 'The Four Horsemen' which appeared on an excellent Vertigo sampler called 'Suck it and See'. Both tracks are from their 1972 '666' album. From this band sprang two figures of note; Demis Roussos, who made a good living singing ballads in his extraordinary voice (he was once referred to as the singing tent) and Vangelis O. Papathanassiou, who had broadened his horizons by composing soundtracks. 'L'Apocalypse des Animaux' was one such; haunting and serene in places like a mellow Tangerine Dreamscape without the sequencing. It was re-issued in the UK in 1976. Vangelis was also responsible for a single called 'Who' under the name of Odyssey in 1974; this is (or can be) a captivating track founded on a drum machine and two chords that go backwards and forwards like a child on a swing while an unknown singer picks out a delightfully understated tune with a haunting chorus. All attempts to cover or remix 'Who' fall short of the original.

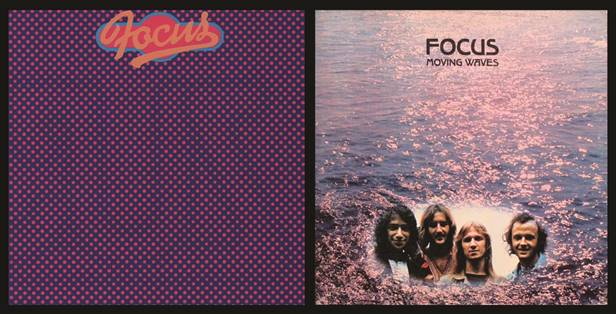

The second Focus album, imaginatively named 'Focus 2' in the Netherlands, was re-titled 'Moving Waves' and released in the UK by Blue Horizon records who were better known for their blues catalogue but the popularity of the LP led to its issue on Polydor who bolstered sales further by issuing the dynamic and quirky 'Hocus Pocus' as a single.

Moving Waves was an effective blend of guitar and keyboard with almost jazz-like drumming. Although Focus were primarily purveyors of instrumental music, keyboard man and flautist Thijs Van Leer dispensed with ideas he might have had about being a singer and found novel ways of using his voice that served as a gimmick and got them heard on the radio and an appearance on the Old Grey Whistle Test. Their first album had lacked the inspired melodies and inventiveness of Moving Waves but Focus 3 was already in the pipeline and promoted by the single 'Sylvia'. Indeed, a double album that allowed the musicians more space to improvise, Focus 3 nevertheless was built on valid musical themes and ideas and is thoroughly recommended if you don't have it already. Guitarist Jan Akkerman quit for a less-hectic solo career but Van Leer has carried Focus for half a Century, discovering new and amazing Akkermans (or is it Akkermen?) along the way.

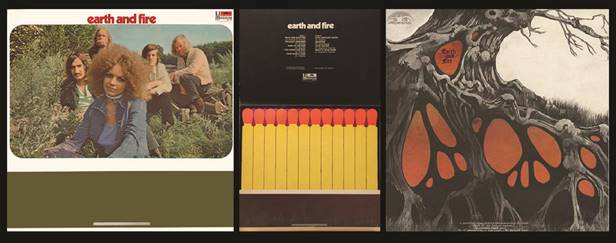

A friend, slightly younger than me, was looking at some records in our lounge and came upon one by Earth & Fire:

"Was that after Wind left?" he enquired.

Earth & Fire had started out as a girl-fronted pop group in Holland (not unlike Shocking Blue of 'Venus' fame) but they moved into a more progressive mode and took to the trail that Focus had blazed. However, my school friend and I were well ahead of the game. Stuart had heard a track on a Dutch radio station that he picked up on medium wave. He didn't speak Dutch but thought the DJ had said 'Earth & Fire'. On our next venture to Virgin in London we found what appeared to be two Earth & Fire albums; both eponymous; one had a slightly shabby-looking sleeve that was made to look like a book of matches while the other one showed an elaborate drawing of the roots of a tree (later identified as the work of Roger Dean). Perhaps through indecision, Stuart bought something else entirely on that occasion but was soon prompted to write to these Virgin Records people and ask whether the Earth & Fire album with the 'tree' cover was still available. It was, and a copy was ordered and duly arrived with a note on the packaging that said; 'Earth & Fire, cover with tree'.

The eventual explanation for the apparent anomaly was that the matchbook cover adorned the Dutch issue while the die-cut Dean-designed version had been released in the UK by a label named Nepentha. The UK issue was to become a much-sought rarity, probably approaching four figures these days. Strangely though, I don't remember hearing the album at the time (the songs on it became familiar much later in life) and I wonder whether Stuart parted with it simply because he didn't like it. I'll ask him next time I see him.

I also got me an Earth & Fire album; their second which is called 'Song of the Marching Children' and I still have it fifty years on. It's not worth heaps of money but it is one of those possessions that become like an auxillary limb or organ.

In retrospect, Earth & Fire's first three albums echo those of Focus; the second and third representing the band at its freshest and most inspired. The album we came to know as 'Atlantis' was a complete re-package of the Dutch release which had been called 'Maybe Tomorrow, Maybe Tonight' which is, bluntly, a dreadful title for a progressive rock album. However, the song of that title was issued as a single in the UK to promote the 1973 'Atlantis' LP though neither took off and the music was to change into something that lacked the almost-childlike rawness of the early stuff.

Other Dutch bands that trod the path included jazz-rockers Alquin who made two pretty decent albums ('Marks', 1972 and 'Mountain Queen', 1973),Golden Earring who cracked the UK singles chart in 1973 with 'Radar Love' and the prog band Supersister who, for one reason or another, I never got to hear. John Peel, whenever asked about Focus, would always say that he preferred Supersister though I must have missed the shows in which they'd been featured.

To round off this little Euro-jaunt and indeed this protracted whistlestop tour of the early 70s rock scene, a band from Norway and one from Finland:

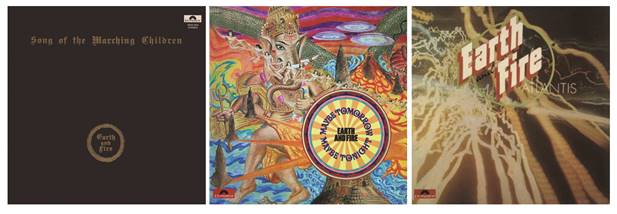

Titanic's 'Sea Wolf' LP was a very early purchase, perhaps one made impulsively; I was familiar with the instrumental track 'Sultana' which had been a surprise hit in the UK and got the Titanic crew on Top of the Pops. Nevertheless, it wasn't necessarily a tune that made you say 'I'm getting that' so the impulse maybe came from the five cool dudes on the cover or the impressive Titanic logo. In the fullness of time I would concede that some of the tunes on Sea Wolf owed much to other bands I'd yet to hear, but as a rock starter-pack, the album had all the required elements; a solid beat with added congas or shakers, natty guitar-work including a fabulous solo on the title track and an inventive production with clever-though subtle use of effects. The vocals of Scouser Roy Robinson (yes, in an otherwise Norwegian band) were easy on the ear if a little difficult to understand in places but as a sampler of what rock music could offer, I might have done a lot worse.

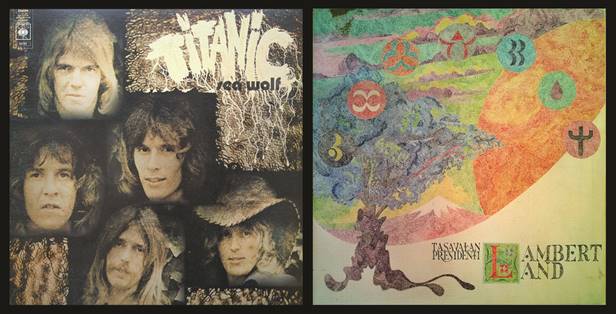

The Tasavallan Presidentii came my way through Subway. There is no obvious reason why the third LP by a Finnish jazz-prog outfit would become a favourite among the personnel at this little record shop but it did. There was something in the exuberance of the music and vocals on 'Lambertland' (1973) that lifts the spirit in ways we don't anticipate. In the age of the internet, we can easily find those previous albums or the ones we heard about but never heard. It is often very easy to say 'this was Titanic's best album' or 'Tasavallan Presidentii's finest hour' when the ones you miss turn out to be disappointing but our judgment is inevitably going to be prejudiced by our personal experience of the time.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In the early 70s, the distinction between black music and white music was understood though rarely drawn. In my little world this distinction was spelt out by the appearance of the monthly magazine Black Music and the weekly newspaper Black Echoes. But these lay in the years ahead and in 1973, the Temptations sat side by side in the record rack with Alice Cooper and Cluster. Selecting nine albums from the soul genre of 71 - 76, it can be observed that all the artists are American and at least 90% male. It is logical that the best soul music was American in much the same way that the best Krautrock came from Germany but the gender imbalance was in parallel with that of the rock world.

Wattstax: The Living Word is the soundtrack to a film of a huge concert by artists on the Stax label, which, according to Discogs, was held at the L.A. Coliseum in August 1972 before an audience of 110,000 who all paid just a dollar to attend. The name is obviously a nod to Woodstock Festival which had been three years earlier but the community spirit encouraged from the stage is in tune with the civil rights movement and the pervading spirit of Martin Luther King despite there being very little of a political nature in the music or dialogue.

I don't remember where I acquired my copy of Wattstax but it had a flaky cardboard sleeve with a hole punched through it which I ascertained to be symptomatic of an American import. The soul music that had flourished in the sixties had moved forward and had fashioned a new element; the funky element. Proper pop historians would, I'm sure, ascribe the development of funk largely to James Brown amongst possible others, but by 1972 everyone had to be funky. Interestingly, the only solo female artist on the Wattstax bill, Carla Thomas is the only act that you wouldn't describe as 'funky'. Carla was best known for her 'Tramp' duet with Otis Redding who died in a plane crash the year it was recorded (1967) and her Wattstax set consists of sentimental ballads from that era. However, her father, Rufus Thomas put being funky above all else. The Bar-Kays, the Staple Singers, Eddie Floyd and blues-man Albert King were new names to me; only Isaac Hayes was well-known in the UK for his 'Theme from Shaft' but his Wattstax set consists of an extended version of Bill Withers' 'Ain't No Sunshine'.

Sly & the Family Stone also played a part in the evolution of funky music as well as pioneering the use of a rhythm machine. They had performed at Woodstock and their hit, 'Dance to the Music' contains the line 'All we need is a drummer for people who only need a beat'. The 1971 album, 'There's a Riot Going on' was unmistakably soul music but with that squelchy bass and Sly's drifting keyboards and his extraordinary voice.

Thus, the soul music of the previous generation, exemplified by Tamla Motown and Atlantic, had morphed into this funk thing just in time for the new kids. Our soul music had that new groove; it was often overtly political but it was first and foremost funky. Frequently though, the artists that were grabbing our attention were the same artists as had entertained our elder siblings; they just adapted to the changing sound and the changing public mood in respect of current affairs (Vietnam, Watergate etc.) and in particular the Civil Rights Movement. The outstanding examples of this are the Temptations, Stevie Wonder, the Isley Brothers and Marvin Gaye. These artists had, in a sense, earned the right to speak their minds and while there was a public apetite for this new social consciousness, the record companies were happy to let them do so.

It is quite important to add at this point, that the two Basingstoke schoolboys on their musical voyage of discovery did not only amass these amazing LPs; we both had singles collections as well. These were less suited to homework sessions because they required changing every four minutes or so but some of the songs and tracks worked better in isolation or amongst other artists rather than on an album by the same one. Besides, 45 rpm records are lovely things, and you can quote me on that.

Those newly funked-up and politically fortified Motown artists arrived on 45s, just as they had done in the sixties but these tunes also served as heralds of 'the album' from which it was 'taken' and, in a few notable cases, were edited versions of longer (and deeper) tracks.

The Temptations had stamped their brand in the UK with numerous, mostly sentimental hits. 'Papa was a Rolling Stone' had immediate appeal; an unrelenting wah-wah groove with those now-familiar voices in a tirade against fecklessness among their own people. The album version was longer; a lot longer and it gave their music a new gravitas. Many of its elements were borrowed from (or shared with) those of their rock peers; preoccupation with war, injustice and corruption and an understanding that kids were perfectly capable of enjoying a song that occupies the entire side of an LP.

'All Directions' (1972) was at the foot of my learning curve. It had that extended 'Papa' and the haunting 'Mother Nature' which must surely be among the first ecology-conscious songs of our time, but other tracks carried that earlier romantic element and some harked back even further to their doo-wop roots. The Temptations' best-known protest songs - the blunt and to the point 'War', the eerie paranoic 'Take a Look Around' and the epic 'Ball of Confusion' - were spread across previous and later albums but nevertheless often made their point adequately on 45s.

Stevie Wonder had earned his stripes as a child prodigy and writer of memorable love songs before he really began expressing his ideas about the world as he 'saw it' through his non-functioning eyes. A human being (particularly an artist) that cannot look outward must inevitably explore the images that manifest within his mind and this was a theme that Stevie Wonder returned to at intervals between full-on condemnation of America's politicians and more of those love songs he was so good at.

Most aficionados are in agreement that the string of albums Stevie Wonder made between 1971 and 1976 (hey, that's my school years) represent his artistic peak but, as I seem to be reiterating; this rule is applicable to every artist in the 1970s. In fact, to have made an album as good as 'Songs in the Key of Life' as late as 1976 merits special attention.

We liked all those albums and played them a lot but all of them had at least one track that I didn't like for one reason or another and 'Songs in the Key of Life' showcases my personal Stevie Wonder favourites (Contusion, Black Man, All-day Sucker and Saturn) along with those that I always chose to skip ('Isn't She Lovely' and 'Knocks Me off My Feet'). Little of Stevie's post-76 work is of any interest to me although later generations joined the train at stations further along the line and will tell an entirely different story, (as is also the case with Bob Marley).

Other funky figures began to appear as the decade progressed; (Curtis Mayfield, George Clinton) but it was the bredth of the new funky wave that appealed, not usually one specific artist and the 7" single introduced us to more perhaps dance-orientated or otherwise less grave and plaintive artists like Kool & the Gang and the Fatback Band. The stories of the latter two and those of many of their contemporaries (the Commodores, Earth, Wind & Fire, the Jacksons, George Benson) tell the story of the birth and death of funky music, for although there were die-hard funksters that defied it; (the JBs, Funkadelic) disco took over and funk gave way to the less syncopated rhythm of the dance floor and thus shed much of its blokeyness. This was the bandwagon on which ABBA and the Bee Gees were to climb and those soul roots seemed a long time gone.

Before departing from the soul department, let me recommend 'Skin I'm In', the 1974 album by the Chairmen of the Board which is too often passed over in top 100s of this and that, probably because it didn't sell very well and was quite challenging by comparison with the chart-friendly hits on which their reputation was built. 'Skin I'm In' was a curious blend of out and out dance floor funk and intimate bedroom soul with some unexpected yet very welcome rock elements. I only recently learned that the fuzzy bass and guitar in the track 'White Rose/Freedom Flower' were supplied by two key members of Funkadelic. The title track 'Skin I'm In' is different again; closer to the rebellious protest funk of the era. This and the Chairmen's previous outing, 'Bittersweet' demonstrate the odd fact that the three vocalists rarely sang together and appeared to agree as to which of them was to be the singer of any particular song. I'm sure there is a lot more to it than that but the curious up-shot of this phenomenon is that irrespective of which of them takes the vocal; it always sounds like the Chairmen of the Board.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

This funk phenomenon was also adopted by American jazz artists. These came to our attention via a character named Lawrence who worked part-time at Subway. I have no idea where he learned about these records but Subway was well-stocked with the works of Chick Corea and Return to Forever, Hubert Laws and Larry Coryell. Though never a fan of jazz more generally, this new funky breed offered a door into the genre. Jazz playing seemed so much more listenable in a funky context. Other artists that popped out included Miles Davis, flautist Herbie Mann and English guitarist John McLaughlin. The first solo album by drummer Billy Cobham, 'Spectrum' (1973) was led off by the furious four-minute 'Quadrant 4' which features a remarkable solo by rock guitarist Tommy Bolin. Weather Report's 'Sweetnighter' LP (1973) was another in-house favourite; carried by an unusual but infectious 6/8 groove.

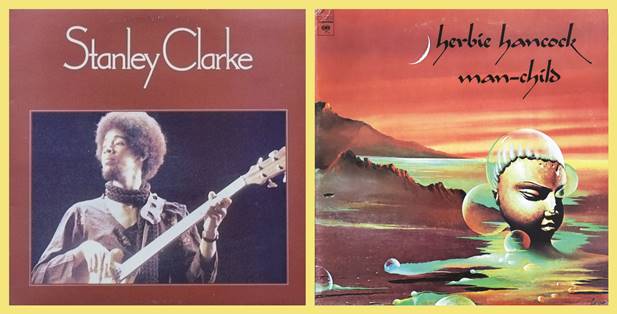

Jazz-funk or fusion as it was often called, elevated bass-player Stanley Clarke and keyboard wizard Herbie Hancock to legend status; both made some splendid albums in the early 70s, often sharing the bill with other jazz players.

Ultimately, my only beef with the fusion funksters was the excessive use of synthesizers which often evoked tortured animals and sometimes spoilt some otherwise very agreeable music.

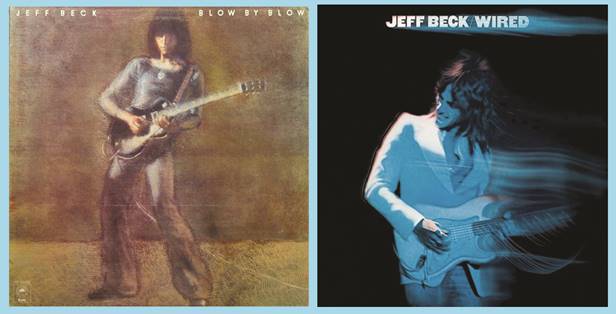

There had been some pretty cool British and European jazz-rock through the early 70s (Soft Machine, If, Ian Carr's Nucleus, Keith Tippett) but these two instrumental albums by Jeff Beck (Blow by Blow, 1975 and Wired, 1976) filled many a half-term holiday. They are, to some extent or other, a British album and an American one. Both have their merits but 'Wired' does include quite a bit of that synthesizer abuse that I mentioned above.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The funk had been adopted in Africa too although Afro-beat music rarely surfaced at the beginning of the decade, excepting Osibisa who aimed initially at a rock audience. I'm not sure when the name of Fela Ransome Kuti first surfaced but I do recall making one of my now almost routine trips to London in search of something called Stern's African Record Shop. I'm sure I saw it advertised in Private Eye rather than a music paper but I found it at the north end of Tottenham Court Road; it was a hi-fi spares and repair shop that did nevertheless have some African records and I'm sure that is where I acquired my copy of 'Expensive Shit'/Water No Get Enemy ' which was effectively a 7" sampler of Fela's side-long Afro symphonies which had been pouring out of Nigeria without our knowledge. I also got a strange 7" EP by the Bokoor Band from Ghana.

Further information came from the monthly magazine Black Music and from looking in industry catalogues. If only we'd had the internet... I bought Fela's 'Alagbon Close' album (1975) but didn't add anything until the 1977 two-LP compilation. 'Expensive Shit', I learned, told the story of how the bandleader and political agitator was arrested on a charge of having used Indian hemp. A sample of Mr Kuti's excrement proved inconclusive. The track lampoons the Police for wasting public money.

In 1976 he dropped the colonial-sounding 'Ransome' and replaced it, at least temporarily with 'Anikulapo' which apparently means 'warrior' but he is now widely referred to as plain old Fela Kuti (he died in 1997).